By Peter van den Dungen, 2020

Since its emergence in the early 19th century, and continuing today, the peace movement has organised countless national and international congresses. Their importance in promoting the development of a culture of peace and strengthening efforts for the prevention and abolition of war, was recognised by Alfred Nobel. In his last will and testament, signed in Paris on 27th November 1895 – 125 years ago – he mentioned ‘the holding and promotion of peace congresses’ as one of three kinds of activity to be honoured by the award of the prize for ‘champions of peace’ that his will instituted. Nobel was influenced and impressed by his friend Bertha von Suttner who was in the forefront of organising such congresses. In June 1902, she inaugurated the world’s first peace museum in Lucerne, Switzerland (together with Frédéric Passy). She wrote to a correspondent, ‘This museum means as much to the peace movement as ten congresses’.[1] Peace museum workers may reflect that if Nobel were to write his testament today, he might well have included peace museums (and their conferences!) as deserving of his prize.

The power of such museums is well documented in the testimony of visitors whose lives have sometimes been radically affected by their visit. This is true for the earliest museums, established by Jan Bloch in Lucerne, and Ernst Friedrich in Berlin, as well as for museums today, especially those in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is also demonstrated by the frequent suppression, by authority and the military, of such museums and anti-war exhibitions. By showing the reality of war, they undermine traditional views on war and the military profession. Even a single artefact – a striking quotation, provocative poster, dramatic photograph, or vivid painting – may have a profound effect. This was the case when Alfred H. Fried, still a teenager, in 1881 visited an exhibition in Vienna when effusive reports in the newspapers elicited his curiosity.

The exhibition, in the famous Künstlerhaus, mainly consisted of paintings of the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) by the Russian artist Vasily Vereshchagin (1842-1904). Many years later, Fried wrote: ‘This visit gave a decisive orientation to my life. Here, I learnt to hate war.

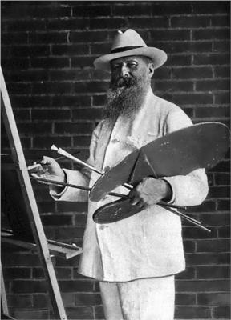

Vasily Vereshchagin

Here, I fully came to realise the horror and misery of war. Today, after four decades, I can still fully feel the revolt that flared up in me when I saw these pictures. There was the pyramid consisting of the skulls of the dead, with ravens at the top, called The Apotheosis of War … And lastly the painting that aroused my anger more than any other: [Tsar] Alexander II who, sitting in an easy chair, with a glowing retinue behind him, all equipped with binoculars and field-glasses, all far from the shooting, observing the course of the battle of Plevna. Below, the death and pain of thousands; above, the master and commander following everything as if it were an interesting spectacle. – When I left the exhibition, I also left behind me all the atavisms which had been fostered in my youth owing to an unscrupulous public education … Now I could see clearly. On this memorable day I left the Viennese Künstlerhaus with a new conviction which, at the time, had not yet a name. I had become a pacifist’.[2] Fried became Bertha von Suttner’s closest collaborator and a pioneer of peace journalism, earning him the Nobel peace prize in 1911.

Von Suttner became personally acquainted with the Russian artist who showed her round another of his exhibitions in Vienna a few years later. She wrote in her Memoirs, ‘At many of the paintings we could not suppress a cry of horror’ and quoted his reaction: ‘Perhaps you believe that is exaggerated? No, the reality is much more terrible.

The Apotheosis of War

I have often been reproached for representing war in its evil, repulsive aspect; as if war had two aspects, – a pleasing, attractive side, and another ugly, repulsive. There is only one kind of war …’ When she said, ‘you were blamed for depicting the most horrible things that you saw’, he replied, ‘No. I found much dramatic material from which I absolutely recoiled, because I was utterly unable to put it on the canvas’. For instance, he had been unable to finish a picture of the aftermath of the third assault on Plevna, where his younger brother Sergey was killed; the place ‘reminded me of Dante’s pictures of hell’.[3]

The exhibition that changed Fried’s life welcomed nearly 100,000 paying visitors in less than a month. The painter had convinced the city government and the art gallery that young people should also be admitted, and he urged low entry fees, with free entry for school classes and soldiers. Even though the Austrian Ministry of War forbade soldiers to visit, they came in large numbers. Because of the extraordinary and unprecedented interest, the exhibition was extended by four days. At the instructions of the artist, the extra income went to the city’s poor, and some of it to the pension fund of the employees of the Artists Union. It has been said that the ‘success was probably without a parallel in the history of art exhibitions by a single painter. For a whole month the public poured into the rooms at an average rate of certainly not less than eight thousand a day (on the last day twenty thousand passed or tried to pass through the rooms) …’.[4]

The same exhibition was equally successful when shown in Berlin when 134,000 visitors came (including the Kaiser) and 45,000 catalogues were sold. Never before, in Vienna or Berlin, had there been such a successful art exhibition. Later in the decade, his paintings were shown with similar success in New York, Chicago and other U.S cities (1888-1890). It was the first solo exhibition for any Russian artist in America and the reviews were hyperbolic in their praise. The public were moved by his anti-war works which reminded them of the sufferings caused by the American Civil War (1860-1865). General William T. Sherman (1820-1891), American commander of the Union troops during this war, proclaimed Vereshchagin ‘the greatest painter of the horrors of war that ever lived’. It is hardly surprising that when the exhibition was shown in St. Louis, young people were prohibited from entering because the paintings elicited such a revulsion against war among many visitors.

From the Napoleon I in Russia series, On the big road

The Apotheosis of War (1871) belongs to the Turkestan series, paintings of the Russian campaign in Turkestan, 1867-68. The frightful scene is not a figment of Vereshchagin’s imagination but relates to the brutal wars of conquest by Tamerlane (Timur), the middle-Asian ruler of the 14th century whose incessant military campaigns resulted in the slaughter of an estimated 17 million people. In central Asia, the custom of commemorating victories by piling up skulls of the slain was one of the most ancient and familiar practices of great conquerors. Initially, Vereshchagin had intended to call the painting, Apotheosis of Tamerlane, but the drama of contemporary politics (the Franco-Prussian war), inspired him to this generalised formulation. On the frame of the painting he inserted, ‘Dedicated to all great conquerors: of the past, present and future’. Many of his paintings resulted in accusations of slander and defamation of the Russian army even though they were based on the artist’s direct personal observations. He burnt several of them, including a painting showing vultures by the side of the body of a dead Russian soldier which caused much offence.

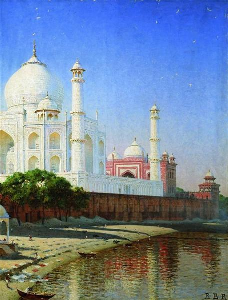

Taj Mahal Mausoleum

His Napoleon series – about the disastrous campaign in Russia in 1812 – was shown throughout Europe in the last years of the 19th century. The paintings depicted the human side of the retreat of the Grand Army from Moscow – ‘the greatest catastrophe in war that has ever appalled the human imagination’. In one of his exhibition catalogues, Vereshchagin wrote, ‘However greatly the Russians may have suffered, their condition was not to be compared with that of the enemy. It is sufficient to mention that the French ate those of their compatriots who succumbed through hunger, roasting them at the bivouac fires’.[5] Vereshchagin was also a prolific author whose books provide important, insightful accounts of his extensive war experience as well as reports and diaries of his numerous travel expeditions (including to China, India, Himalayas, Kashmir, Japan, Syria, Palestine, USA). In parallel with the Napoleon exhibition, he published a book to explain the paintings: Napoleon I in Russia. It destroyed the myth of his unconquerability and resulted in the prohibition of the book in France.

During two lengthy stays in India, Vereshchagin depicted characteristic aspects of Indian life.[6] He painted many outstanding monuments of India’s ancient architecture and sculpture: Buddhist temples and monasteries, Muslim mosques and minarets. Most famous among his Indian landscapes is the Taj Mahal Mausoleum in Agra. Executed with fine artistry, his works inspired an affection for India and her people and depicted the ruthlessness of the British colonisers.

The great English journalist and peace campaigner, W. T. Stead, following a meeting with the artist in London in 1899 (they had first met in 1887), wrote a lengthy article in which he called him ‘a very remarkable man’ and ‘the most famous of all painters of the realities of war … He is a soldier-artist, a man who became a soldier for the sake of his art, and who uses his art in order to teach the world the truth about soldiering’.[7] He does so by showing not scenes of actual combat but the great hardships and sufferings it causes: ‘War means hunger, thirst, sickness, the pain of wounds , privations of all kinds – a reversion to the conditions of savage existence.’ The painter insisted that the worst things in war are so bad as to be unpaintable on canvas (as he also mentioned to Bertha von Suttner).

Stead reported that Vereshchagin was one of the first Europeans to venture into the heart of Central Asia, in the borderlands between Chinese empire and Russian possessions, very soon after the suppression of the Muslim revolt by the Chinese army, a struggle which lasted many years. The artist described how he entered many totally depopulated cities. One left a very vivid impression upon his mind: ‘It was a literal Golgotha, or Place of a Skull, and not of one skull only, but of many heaps of skulls. … in the neighbouring villages, streets and courts were similarly banked up with skulls and skeletons, and in the surrounding fields, so far as the eye could reach, you saw everywhere skulls, skulls, skulls! … That revolt, he calculates, cost from twenty to twenty-five million lives’.[8] It is dispiriting that the 20th century has added its own countless millions of innocents slaughtered – in the Armenian genocide, Stalin’s Gulags, Hitler’s extermination camps, the killing fields of Pol Pot’s Cambodia, Rwanda’s genocide of the Tutsi (1994) …

The credo of Vereshchagin’s work is revealed in a letter to Pavel Tretyakov in 1879: ‚As an artist I am faced by war which I attack as much as I can; whether my blows are effective and strong enough is another question – about my talent. But I strike with utmost force and without mercy’.[9] In 1872 the painter had made the acquaintance of the rich merchant and art collector who bought many of his works; today they can be seen in the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.[10] (More than 200 of his paintings can be seen at https://www.wikiart.org/en/vasily-vereshchagin/all-works/text-list).

Franz Heinemann, a Swiss historian and art expert, used the inauguration of the museum in Lucerne to publish a study, believed to be the first of its kind, which brought together artistic witnesses against war, providing an overview of the iconography of the horrors and miseries of war. It was also meant to show the friends of peace that they had a powerful ally in the graphic arts. He quoted with approval Jan Bloch: ‘In our time, a decisive turning away from war can be observed not only in literature but also in painting’. In the novels of Tolstoy, Zola, and von Suttner, among others, the traditional poetic and enthusiastic treatment of war was replaced by a stark realism, inspiring revulsion against it. Heinemann asserted that the greatest achievement in the contemporary artistic depiction of the horrors of war belonged undoubtedly to Vereshchagin.[11]

In his stupendous six-volume work on the war of the future Bloch likewise greatly praised the painter whose works immediately and powerfully gripped the viewer, leaving an indelible impression. They represented a visualisation of Tolstoy’s unsurpassed pages in War and Peace. Bloch wrote that however shocking Vereshchagin’s paintings were, they were naked reality, witnessed by the artist, or based on authoritative accounts.[12] None of Vereshchagin’s paintings were on display in Bloch’s museum, perhaps because of the latter’s premature death before its opening. The painter himself perished on board a battleship during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) when it struck a mine near Port Arthur (Lüshun, China).

Next year is the 150th anniversary of The Apotheosis of War which belongs in all museums of war and peace as well as military academies and departments of defense. Last month saw the 75th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Iri and Toshi Maruki, in their art and personal experience, are the Vereshchagins of the nuclear age. Their art works, first shown in Tokyo in 1950 and then around the world, had an overwhelming impact. Their large murals have been called ‘the finest artistic protests ever made against the folly of war’.[13] In the campaign for the abolition of nuclear weapons and war, reproductions of their work belong in every peace museum, together with the voices of Hibakusha.

Peter van den Dungen

Bertha von Suttner Peace Institute, The Hague, 2020

[1] Letter to Theodor Herzl, quoted in Brigitte Hamann, Bertha von Suttner: A Life for Peace (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1996, p. 217).

[2] Alfred H. Fried, Jugenderinnerungen (Berlin: C. A. Schwetschke & Sohn, 1925, pp. 12-13).

[3] Memoirs of Bertha von Suttner (Boston: Ginn, Vol. 2, 1910, pp. 10-12). Also see Valentin Belentschikow, Bertha von Suttner und Russland (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2012, pp. 47-60) and the same author’s Im Namen des Pazifismus: Wassili W. Wereschtschagin und Bertha von Suttner (Berlin: Frank & Timme, 2020).

[4] Richard Whiteing in his introduction to Vassili Verestchagin, “1812” Napoleon I in Russia. Illustrated from Sketches and Paintings by the Author (London: William Heinemann, 1899, p. 14).

[5] Catalogue of Paintings by Vassili Verestchagin including The Campaign of Napoleon I in Russia and The Battle of San Juan Hill on Exhibition in the Astor Gallery of the Waldorf-Astoria (New York, 1902, p. 45).

[6] Artists Look at India. V. Vereshchagin [etc.]. Moscow: State Fine Art Publishing House, 1955.

[7] W. T. Stead, ‘Character Sketch: Vassili Verestchagin’, in The Review of Reviews, Vol. XIX, January 1899, pp. 22-33. This important article is absent from the exhaustive bibliography in A. Lebedev’s massive biography, V. V. Vereshchagin (Moscow, 1958, pp. 428). This explains why there is no mention of it either in Vahan D. Barooshian, V. V. Vereshchagin: Artist at War (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1993).

[8] Stead, o.c., p. 28.

[9] Quoted in Regine & Gerd Pfrepper, ‘”Sollen doch jene, die diesen Krieg wollten und in ihren Amtstuben herbei schrien, hierher kommen […].“ Korrespondenzen und Gemälde aus dem Russisch-Türkischen Krieg 1877/78‘ in Wolfgang U. Eckart & Philipp Osten, eds., Schlachtschrecken – Konventionen. Das Rote Kreuz und die Erfindung der Menschlichkeit im Kriege (Freiburg: Centaurus Verlag, 2011, p. 210).

[10] Masterpieces of the Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow: The State Tretyakov Gallery, 1994, pp. 82-85).

[11] Franz Heinemann, Die Schrecken des Krieges im Lichte der bildenden Kunst (Lucerne: Internationales Kriegs- und Friedensmuseum in Luzern, 1902, pp. 3, 30). This rich and passionate study remains valuable.

[12] Johann von Bloch, Der Krieg (Berlin: Puttkammer & Mühlbrecht, Vol. V, 1899, pp. 88-90); Jean de Bloch, La Guerre, Vol. V (Paris : Guillaumin, Vol. V, 1899 ?, pp. 74-76).

[13] James Kirkup in his obituary of Iri Maruki, The Independent, 21 October 1995, p. 22. Also see John W. Dower & John Junkerman, eds., The Hiroshima Panels: The Art of Iri Maruki and Toshi Maruki (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1985).